The Dawn of Streamline Moderne

James Oviatt's Penthouse Bedroom, Oviatt Building, Los Angeles, Photo by Kolby, flickr

The change in styles from the 1920s (which many call Art Deco, although it is perhaps better described as Zigzag Moderne or Jazz Moderne) to the 1930s (Streamline or Art Moderne) was interesting. The two styles are fairly distinct although they are typically grouped together under the banner 'Art Deco'. This is seen most accutely through the beginning of the Streamline Moderne design era.

Jeanette Willette explains that following the financial shock of the market crash in 1929, "the sophistication of Art Deco in Paris and other European nations was simplified and applied [in America], not to objects of desire, but to objects of usefulness. The importance of the appropriation of Art Deco by American industrial designers, as the new artists called themselves, was that suddenly a very high style was extended to new areas of everyday life, suddenly succeeding in bringing good design into the home at affordable prices." (Willette, "Aerodynamics and Streamline Design 1930s, Part One", gathered 6-30-24)

The Great Depression so shocked those living through it that the average person wanted to withdraw their money from the bank, which eventually resulted in cascading bank failures in 1933.

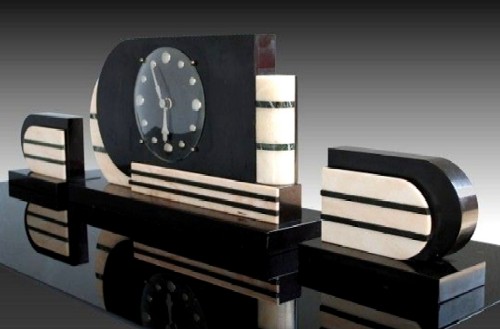

Streamlined Marble and Bronze Desk Clock with Book Ends, 1930s, 1930.fr

There was no protection for money lost because of a bank failure at that time. So people wanted to get their money and have it ready against future market failures. Curiously, 1933 was the same year that the stock market began to recover, continuing to do so for a couple years. The decline which occurred beginning in 1935 didn't occur because there was no money, it was because people were afraid to spend the money they had. Industrial designers made it their business to be part of the solution.

"By dint of having large industrial resources, underutilized as they were during the Depression, America was better positioned to mass manufacture good design than its European counterparts. Germany was crippled by the Depression and the Bauhaus was snuffed out by the rising stars of the Nazi party. In addition to shifting good design to the arena of mass consumption, industrial design applied Streamline Moderne to objects that anyone could afford and that everyone used. ...Affordable, available and stunning to behold, Streamline Design was an American phenomenon that attempted to cajole the public to buy new and stylish products during the Great Depression." (Willette, 'Part One')

Willette points to the Chicago Century of Progress World's Fair of 1933-4 as the introduction of Streamlined 'Machine Age Aesthetic', a style which embraced machines with their clean, purposeful lines and functions. Those of you who read the article on the history of glass blocks may recall that this is where the general public was introduced to the use of glass blocks in home building.

The Century of Progress Home Exhibits/Tour,

Chicago World's Fair Brick House Steamlined Living Room, 1934,

From

A Century

of Progress Homes and Furnishings, Dorothy Raley, ed., 1934, p. 30

which had fourteen free-standing houses designed to "represent a pronounced departure from conventional construction." (A Century of progress homes and furnishings, Dorothy Raley, editor, p. 6, gathered from the internet 6-30-24) Although we think highly of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne designs today (particularly those of us in this group), the change in style appears to have been a shock to the average person at the time. "The public ate up the Homes of Tomorrow exhibit, but only in terms of a fair exhibit. Most of the published comments from fair-goers were positive in terms of enjoyment, but the homes were found to be strange and cold, not places to call 'home.' No one actually wanted to live there." (Christina Branham, "House of Tomorrow: A Machine for Living", my History Fix website, gathered 6-30-24) For an example a Streamlined room which appeared at the Century of Progress Home Exhibits, see the image at left.

The Burlington Zephyr locomotive (later renamed the 'Silver Streak') was also presented at the Chicago World's Fair, designed by aeronautical engineer Albert Gardner Dean. Its tilted front and smooth body "looked unlike any train that had ever taken to the rail. The term used [to describe the Zephyr] in the 1930s was 'streamlined' [which] was later changed to "aerodynamically" designed." (Willette, "Aerodynamics and Streamline Design 1930s, Part Two", gathered 6-30-24) Streamlined designs came from airplanes and the design fascinated the public.

Norman Bel Geddes. considered by some to be the father of streamlining, wrote a fairly detailed article on the concept for the Atlantic Monthly in 1934.

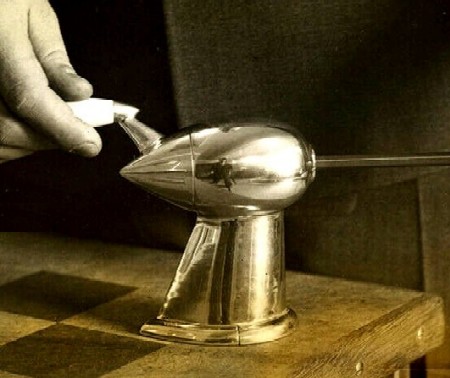

Streamlined Cobra Lamp, Polished Nickel, Norman Bel Geddes, 1930s,

Art Deco Collection

He explained that while streamlining to reduce air resistance was not fully understood by engineers of the time, "advertising copy writers seized upon it as a handy synonym for the word 'new,' using it indiscriminately and often inexactly to describe automobiles and women's dresses, railroad trains and men's shoes." (Norman Bel Geddes, "Streamlining". The Atlantic, November, 1934, p. 553) Bel Geddes proposed a variety of automobiles and ships with streamlined exteriors as well as succumbing to the desire to add aerodynamic 'streamline' designs to everyday objects such as lamps, seltzer bottles and even a child's desk.

This was a break from the style found in the 1920s. Much of what was produced during the 1920s was highly stylized, simplifying the Art Nouveau designs of the previous period and moving from a flowery, ornate simplification to a more rigid, geometric one. Art Deco items in the 1920s were often hand-crafted, built in small numbers for wealthy clients. The 1930s saw design simplification through curvy streamlining with the resulting product being mass produced for a broader market than the 1920s Art Deco designs.

"The America of the Depression is rarely thought of as a place of innovation in design, but the decade was a golden age of industrial design led by the sensational arrival of Art [aka. Streamline] Moderne embodied by a fleet of trains the [sic] announced the arrival of the future. Whether they moved or not, other consumer goods would copy the look of the Silver Streak. Ironically at a time when few could afford gas for their beat up and broken down cars, speed was the slogan of the 1930s and its streaks were imprinted on the new household products." (Willette, "Part Two")

The Modernist Design Impact

Reconstruction of Le Corbusier and Perriands Model Home for Salon d'Automne in 1929,

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Modernist LC furniture, Wallpaper.com

Modernism guided the move towards geometry and simplification. It directed the designer to strip away unnecessary decoration and focus on the functional aspects of a product. While Modernist tendencies are found in the Art Deco 1920s designs, it was only a driving force behind the products of some designers. It is prominently displayed in the interior designs of Charles-Édouard (Le Corbusier) & Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand. See the image at left for a recreation of their designs of a model home for the Paris 1929 Salon d'Automne.

Aspects of stripped down Modernist designs also appeared in the products from the Bauhaus school. Bauhaus built upon a designer's artistic vision while emphasizing function and incorporating principles of mass production in the final design. (Examples of Bauhaus style furniture can be seen in the first image below.) Many Art Deco designs, just about all Art Nouveau designs and most of what preceded them violated the ideals of Modernism. It really came to the fore in Streamline Moderne designs of the 1930s, continuing to be employed in spartan Mid-Century Modern designs of the post-World War II era.

In its purest form, Modernism stripped away nearly everything but what was required for the design to function properly - basically a form of minimalism. While Streamline Moderne designs embraced a more minimalist approach, it also incorporated design flourishes. A commonly cited example of this were speed lines - several parallel lines which sometimes came to a point at one end. These were intended to give the impression of speed,

Pencil Sharpener, Raymond Loewy, 1934

even to objects which had no reason to appear to be going fast. Raymond Lowey's Streamline Moderne pencil sharpener is often mentioned as an example. (See the image at right.) Curiously, this unique design was never actually put into production.

Not everyone saw such decoration positively. Stage designer turned industrial designer Henry Drefuss somewhat sourly commented that retailers sometimes asked him, "'Can you fix this up and make it look pretty?' Indeed for a time in this chaotic period [of the 1930s] a person who knew how to enamel something black and put three chromium strips around the bottom was considered an industrial designer." (Henry Drefuss, Designing for People, 1955, p. 19)

Several artisans creating hand-made Art Deco pieces in the 1920s eventually recognized the value of the Modernist style and its machine-friendly products. From this came the field of Industrial Design with its products designed not just to visually appeal to people, but to serve them through their function, design and less expensive and time-consuming production. Silversmith Peter Muller-Monk delineated the difference between the two types of products: "The pieces which leave my hands should have the virtues of the slow and calculating process of design and execution with which they grew. On the other side, the factory product should reflect the exactness and mathematical economy of the machine that created it." (Peter Muller-Munk, "Machine-Hand," Creative Art: A Magazine of Fine and Applied Art, October, 1929, not paginated). As the prosperous 1920s gave way to the Depression-laden 30s, Muller-Monk embraced the role of Industrial Designer.

Other Design Changes From the 1920s

The transition from Art Deco to Streamline Moderne also saw a dramatic shift in the color palette. The brightly colored jewel tones and dramatic black and white contrasts found in 1920s room designs gave way to more subdued pastels, off whites and

Subdued Colors in Villa Cavrois Boudoir

soft browns. Patrick Baty explains, "Sensory overload caused by clutter and the brightly coloured and strongly patterned wallpapers beloved by the previous generation was sometimes given as the main reason for the preference for straight lines and quiet pale colours in the 1930s." (Patrick Baty, The Anatomy of Color, 2017, p. 270)

Baty suggests that one of the reasons for the change was because "new building methods allowed for the inclusion of larger windows, and a new-found love of nature required interiors to be decorated in sympathy with the view without." (Baty, p. 270) The use of concrete in construction allowed for wider widows and better views of the outside. The use of bright, contrasting colors inside competed with the natural tones of the improved view of the outdoors, creating what Baty calls 'discordant effects'. This meant "that colours should be pale and soft and that works of art should be subordinate to the room rather than dominate it." (Baty, p. 274)

Given all these noticeable differences in style, color, inspiration and production, it is not entirely clear why two such different styles are consistently included under the broad heading of 'Art Deco'. While they both embraced a movement towards Modernism, they also have many distinct, unique facets. Add to this the significant change from the artisan craftsman creating modern pieces for the wealthy few in the 1920s to the creation of the industrial designer creating modern pieces for the masses in the 1930s and you can see that there were two very different styles in this short period.

Other Sources:

"Century of Progress Homes Tour", National Park Service website, US, gathered 6-30-24

Erika Dahl, "Century of Progress Homes from the 1933 World's Fair in Chicago", South Shore CVA website, gathered 6-30-24

Original Facebook Group Posting 1, Original Facebook Group Posting 2