Lucie Renaudot (c. 1895-1939)

Lucie Renaudot was a French decorator and designer of furniture who was active during the Art Deco and most of the Streamline Moderne (aka French Paquebot) periods.

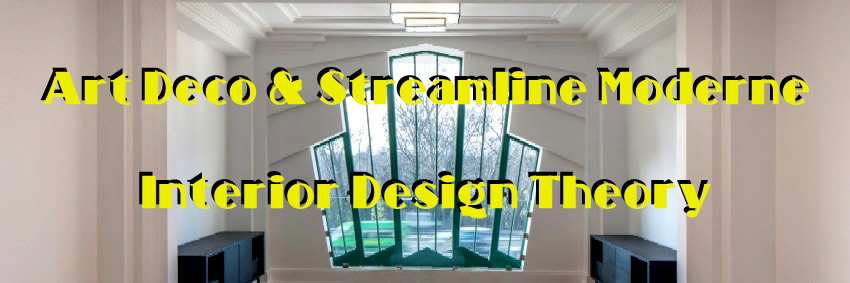

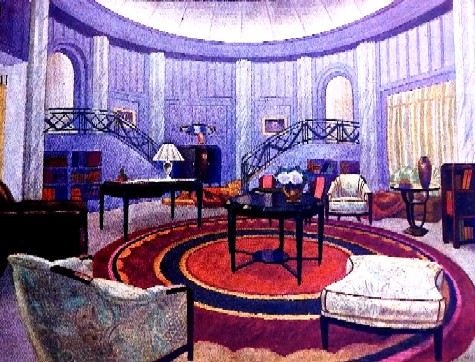

Living Room, Salon des Artistes Décorateurs, 1929, Interieurs IV, Plate 3

Little is known about her early life and education other than she was born in Valenciennes, France. Even the year of her birth is not certain. One French source notes that she had no formal training in design either from schooling or apprenticeship.

She married painter Paul Renaudot, although the date of their union is not known. He died in 1920, just as her career was beginning to blossom. The announcement of his death in Montparanasse: hier et aujourd'hui noted that he was "prematurely taken from the affection of his wife, Mrs. Lucie Renaudot, a talented decorative artist." (Jean Emile-Bayard, Montparanasse: hier et aujourd'hui, ses artists et ecrivains etrangers et francais les plus celebres, 1927, p. 299)

Renaudot's first design commissions came from tea rooms Tipperary and Ça Ira around 1918. Writing about these projects several years later, Gabielle Rosenthal explained, "She made the seats and small tables of lacquered wood, which is inexpensive and easy to maintain. Above all, she strove to create atmosphere. The resources available to the artist were measured; but she is a woman. And she painted flexible garlands on the walls that divide them into panels, and, at the top of a luminous cornice, she cheerfully planted a basket of flowers. It become smart, conducive to chats and sharing confidences." (Gabrielle Rosenthal, "Creatices D'Art Moderne: Lucie Renaudot", L'Art Vivant, May 15, 1926, p. 11)

Renaudot's comments about design hint at an intuitive approach to her chosen field. "Certainly, the work of the decorative artist is admirably suited to women, and if she is gifted, intelligent and hard-working, she can create a superb position for herself, but she must never shrink from responsibility and work." (Francoise Vitry, "Enquetes, La femme dans l'evolution de l'art apres la guerre", L'Opinion: Journal de la Semaine, November 13, 1926, p. 17) Magazine profiles from the period suggest that while she didn't start designing her own furniture, she began to do so around 1921, further reinforcing the idea that she learned the profession as she went along.

Renaudot established a working relationship with cabinet maker

Lucie Renaudot (attributed), Bookshelf, Mcassar Ebony Veneer, Ebonized, Silver Hardware,

c. 1930, Proantic

Paul-Alfred Dumas, designing furnishings for him from 1919 until her death in 1939. Jean-Marie Gauvreau explained the Lucie ran Dumas' 'drawing workshop' "with undeniable success". (Jean-Marie Gauvreau, Nos Interieurs de Demain, 1929, p. 36) "Mr. Dumas was lucky to take on Mrs. Lucie Renaudot as a collaborator. One only has to browse through decorative art magazines or works on the same subject to find the identical and unanimous praise given to her exquisite feminine sensitivity". (Gauvreau, p. 44) Paris-based furniture manufacturer Maurice Rinck also produced some of her furniture. Designers often sold designs for individual pieces and lines of furniture to one manufacturer while working for another.

An important part of being a new designer was publicity. As Renaudot explained, "The most difficult thing, like everything that touches on art, is to get yourself known. To do this, you have to exhibit your works, try to show them by all possible means, and if they are remarkable, it is not the public who will be enthusiastic at first, but the people in the trade, and the important houses who will guess what will be successful, will then place important orders." (Jeanne P. Crouzet-Ben-Aben, "l'Enseignement secoindaire des Juenes Filles", Revue Universitaire, Volume 35. p. 444) As a woman in a male dominated field, publicizing her work was particularly important.

Decorators in the 1920s and 30s had several methods for publicizing their work. The first was to advertise

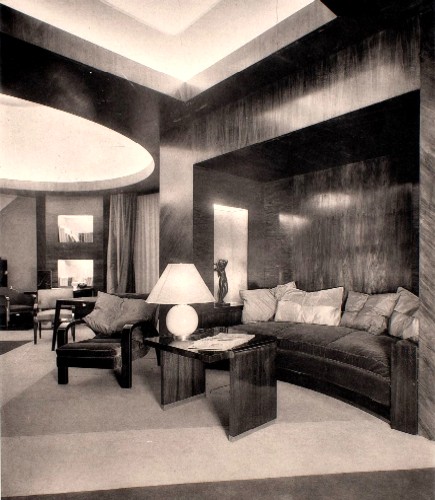

Nursery, Ambassade Francaise, Exposition Internationale des Arts

Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, Paris, 1925, RIBAPix.

their skill at exhibitions. Renaudot made her 'public' debut at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1919. She continued to create displays for them in the ensuing years, becoming a furniture designer for her Children's Room at the 1921 salon. Her first display at the Salon des Artistes Decoratifs was in 1923 which was probably when she joined the Societie. Her next display with the Societie des Artistes Decortifs was at the 1925 l'Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes. For their 'house of French ambassador who lived abroad', she designed another children's bedroom, which can be seen at left. In 1926, she created a bedroom design for a spring salon which received a medal from the Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale. A living room she designed for Maurice Rinck at the 1937 Paris World's Fair's 'International Exhibition of Art and Technology in Modern Life' won the Grand Prix. (This is the purple room which can be seen below on the right.)

A second way for a designer to advertise was by having their work published in magazines and books. As suggested previously, Renaudot received quite a bit of publicity in design magazines beginning as early as 1919 in an article about the Salon d'Autumne. Among the many magazines which mentioned her and included images of her work during her 20 years of design activity were L'Art Vivant, L'art décoratif, L'amour de l'art, Lux: la revue de l'éclairage, Revue Universitaire, La Esfera, The Upholsterer, Town & Country and Interior Decorator, Good Furniture Magazine and Interior Decorator, Good Furniture Magazine and The Studio. In 1921, she created watercolor images of rooms and furniture for a special insert Furnishings and Interiors in the magazine Gazette du Bon Ton.

Probably the best method for designers to have their work promoted was through word of mouth from the clients who hired them. This typically required the artist to be well-known enough to garner the interest of such clients through displays at exhibitions, subcontracted work for other design artists and architects and coverage in publications. Renaudot is perhaps a bit unusual in that her first known design work was for two tea rooms in 1918 as mentioned previously.

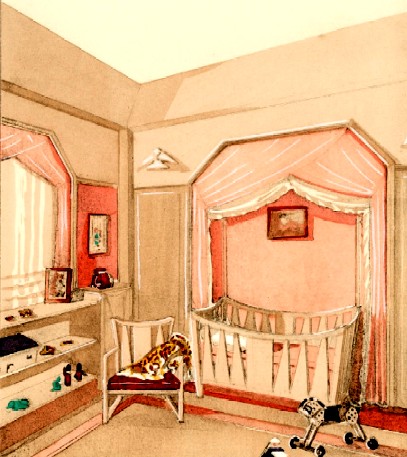

Lucie Renaudot, Normandie 1st Class Exterior Cabin, 1932, Tessier Sarrou.

During the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne periods Lucie was also commissioned to design for individual clients. Writing in 1926, one article noted, "She has thus designed more than 300 interiors in less than a year, based on her own designs and ideas." (Vitry, p. 17) She designed rooms for houses in Paris and Alsace as well as some of the state rooms for the 1935 French ocean liner Normandie. (See the image at right.)

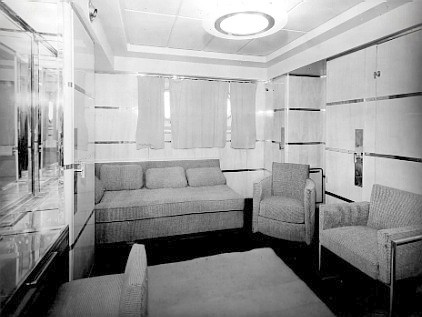

Of her style, author Alastair Duncan says it "was classically inspired, part English Regency and part Louis XVI. A gentle formality predominated." Writing in 1924 near the beginning of her career, Leon Moussinac notes her style as a "simple but subtle play of surfaces and lines, where light adds to the effect of precious materials and to the grace of a curve in a piece of well-proportioned furniture." (Leon Moussinac, 'Introduction', Interieurs III, 1924, not paginated)

Gabrielle Rosenthal explained, "In this revival of decorative art, where so many strange and foreign influences invade us, Madame Lucie Renaudot has made a place for herself of logic, elegance, and French grace." (Rosenthal, p. 11) She goes on to point out modern characteristics of Renaudot's furniture, particularly its 'geometricism' with an added feminine touch. Such "ingenuity is obvious to discerning women". (Rosenthal, p. 12)

Duncan notes that she received very little criticism in the popular press during her lifetime despite her tendency towards conservative design. He does say that her room ceilings are frequently quite interesting and unique for the time, featuring "circular or square recessed frosted paneling to provide concealed lighting." (Duncan, "Introduction", not paginated)

Perhaps the most fascinating part of Lucie Renaudot was that she was a recognized and sought-after female room designer. Although there were a number of women involved in the design of home decor during this period in France, most of them were not recognized for creating entire rooms like Renaudot. (Some of them were doing so without recognition. See the article on Charlotte Perriand for example.) Several of Renaudot's comments from the period reveal her thoughts on this:

Lucie Renaudot, Studio, Fom Leon Deshairs, Interieurs en Couleurs, ca. 1926, Plate 15.

"The current difficult life has taken it upon itself to make us [women] practical artists. We had to do something with our dream; we could no longer be content with being amateurs. ...This career is moreover exciting; it is full of promise, and women who are just beginning to enter it now will be right to choose it, because they can succeed admirably, thanks to their taste, their skill, their imagination.

...

It is also a very tiring profession, because one must stand for whole days, to supervise the workers and follow them step by step in their work, if one wants the furniture, the woodwork, the entire room to be made exactly according to the plans and drawings provided. The feeling for proportions is instinctive, and the woman's brain is just as productive as that of the man: Alone in a jury of men, I imposed my ideas on them... Yes, we can make a very nice situation for ourselves as decorators, it is therefore interesting from all points of view; as gain, as work and as enjoyment of self-esteem; but let us not hide the difficulties; a woman has to fight terribly to defend herself; she must conquer her place, not only by dint of talent, but by dint of tenacious and intelligent will; without this, it is to be feared that she will be paid less than a man and that she will be treated in negligible quantities. Once she has achieved fame, when she has overcome this sort of distrust that men have for women who work, and especially for women artists, she is saved. Because then she is respected and her merit is loyally recognized. ... 'When a woman has conquered,' says M. Renaudot, 'this sort of distrust that man keeps towards the woman who works, and especially towards the woman artist, she is saved. For then she is respected and her merit is loyally recognized.'" (Crouzet-Ben-Aben, p. 444)

However, Renaudot also touches upon the necessity for practical consideration when pursuing such a career. "Nothing is more feminine, more charming, more pleasant for a woman than to create in this way the framework of an intimacy. But we must not forget that these fanciful designs, which require a continual search for invention, must be based on a true architectural science." (Crouzet-Ben-Aben, p. 444)

Other Website References:

Lucie Renaudot, Artvee

"Our History", Rinck

Ribambins, "Lucie Renaudot: chambre d'enfant Art Déco. Exposition 1925",.Ribambelles et Ribambins Blog

Ian Phillips, "Out of Rinck’s Vast Antiques Archive Comes Innovation", 1st Dibs

Jean-Marie Gavureau, Nos Interieurs de Demain, 1929, Digital BAnQ

Original Facebook Group Posting

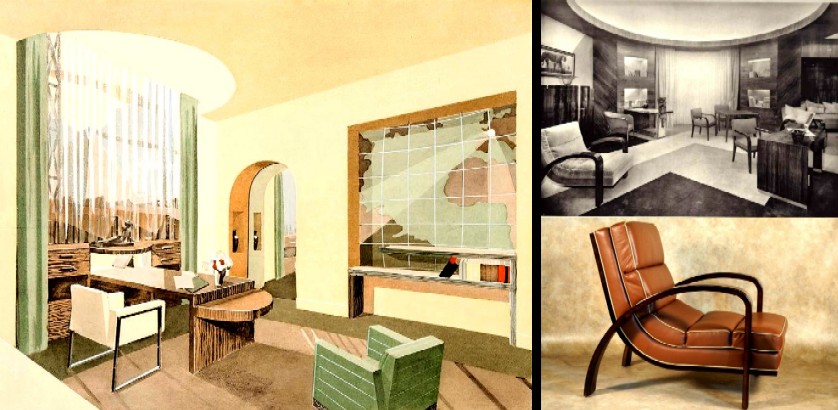

Lucie Renaudot Designs, From Left: Office for Mme. L. du Stic, 1920, Artvee; Lucie Renaudot, Salon des Artistes Decoratifs, Interieurs d'Aujourd Hui, 1928 with example of a Chair from the Room, 1929, 1st Dibs

Lucie Renaudot Designs, From Left: Office for Mme. L. du Stic, 1920, Artvee; Lucie Renaudot, Salon des Artistes Decoratifs, Interieurs d'Aujourd Hui, 1928 with example of a Chair from the Room, 1929, 1st Dibs