Andrew Denham Maclaren (1903-1989)

Andrew Maclaren was the son of wealthy parents Andrew and Eve Maclaren.

Andrew Denham Maclaren, Early 1920s

One account suggests his 'second name of Denham' came from the original name of the house where he was born (called 'The Cedars'), which was Denham Cottage. Maclaren attended Malvern College between 1917 and 1920. Following this, he attended Académie Julian in Paris in 1920-1. He then enrolled in Jesus College, Cambridge in 1922, passing his exams in engineering in 1924 but not graduating. He played ice hockey for Cambridge and distinguished himself in boxing. He helped Cambridge defeat Oxford as a light heavyweight boxer in 1924. In 1925, he spent a year at Slade School of Fine Art in London. He enrolled in Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Acadaemy of Fine Arts) in Munich, spending 5 months there before returning for another year at Académie Julian in 1926-7. He furthered his education through travel; going through parts of Europe and North Africa in his teens and twenties, getting exposed to other styles of art, design and architecture.

Maclaren went to work for property developer and designer Arundell Clarke at his company Arundell Display in 1927, continuing there until 1930. He designed furniture and decorated homes for private clients as well as executing exhibits for Clarke. Maclaren was eventually promoted to a director position at Arundell. Through Arundell Display, he was assigned to design a bathroom for the 1928 exhibition Modern Art in French and English Furniture and Decoration at Waring & Gillow's Oxford street store. It was Modernist in style, featuring black, red and white colors, a black porcelain bathtub and toilet, glass shower door, metal doors and shelves and a tubular metal seat.

In 1929, Maclaren left Arundell to form his own studio, listing himself as a architect and decorator. His work appeared in magazines including The New Interior Decoration and The Architectural Review. The latter magazine staged a contest to promote interior decoration. Maclaren designed furniture and light fixtures for an entry, with designer Paul Nash creating carpeting and fabrics and artist Edward Wadsworth contributing paintings. Their entry placed second, with the judge noting that their "design shows a truer architectural quality than any other submitted". (The Architectural Review, November 1930, p.203, cited by cited by Duane Kahlhamer, "Denham Maclaren (1903-1989): Furniture and Interior Designer", The Journal of Decorative Arts Soceity 1850 - the Present, 2021, p. 155)

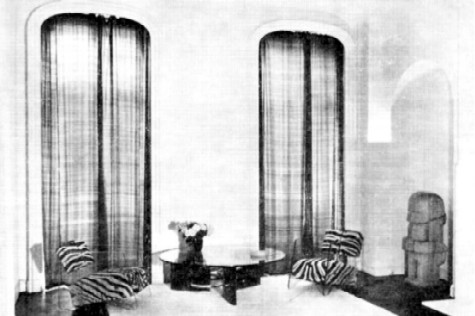

Reception, 52 Grovsner Street, From Harper's Bazaar, June, 1931, Gathered from

Design Masters Auction Catalog, Phillips de Pury and Co., 12-15-10, not paginated.

His glass-sided chairs and table top can be seen here.

In 1929, Maclaren purchased a four story building at 52 Grosvenor Street in Mayfair thanks to a loan from his mother. His goal was to divide the building into apartments and design the rooms and furniture. He worked on the renovations between 1930 and 1935, adding the necessary bathrooms, a new light and power systems and an elevator in addition to redecorating the structure. Following his conversion of the former house, there were two flats and a room on the third floor and three flats on the second. After 1933, the ground floor held two shops in the front, one large and one small, and the Garter Club in the back. One ancestry website says that Maclaren "[o]wned a night club that was famous for having two tigers/panthers and orgies." ("Andrew Denham Maclaren," Ancestorium Family Tree Collaboration, gathered 3/25/24) This is probably a reference to the Garter Club, which he did not own. (It also sounds rather doubtful, but who knows?) Maclaren lived in a flat located at the back of the building in the basement, rented out the other flats and commercial space. The remodeled contemporary reception room on the first floor of the building was featured in Harper's Bazaar in 1931, showcasing his Modernist windows and furniture. (Seen at left.)

During the early 1930s, Maclaren worked on private commissions for clients, including architect Norah Aiton who subscribed to the Modernist style. Around 1935, he began selling his designs through decorator Duncan Miller,

"Seagull" Surrealist Table, Painted Wood and Glass, Deiign Masters Auction, Phillips de Pury,

12-14-2011, 1936

continuing to do so until at least 1937. In 1936, he began move away from the well-defined geometrical Art Deco style, incorporating aspects the flowing aspects of Surrealism into his designs. This corresponds somewhat with the Streamline Moderne design theory which focused on curves rather than hard edges, but his designs were more abstract.

Maclaren married Nancy Jones in December of 1934. During their time together, he became interested in photography and began experimenting with lighting. He took photos of Nancy and other women exploring this. Duane Kahlhamer suggests that this was an attempt to explore Surrealism, for whom "techniques like photomontage and collage, offered ways of exploring the unconscious mind." (Kahlhamer, p. 165) His interest in photography corresponded to a loss of interest in interior design. Maclaren separated from Nancy in 1938 and, by his own account, ceased designing that same year. They finally divorced in 1942.

What happened in his later years is difficult to determine. According to Kahlhamer he enlisted in the service during World War 2, but "returned to civilian life after war service with a changed outlook and priorities." (Kahlhamer, p. 166) In 1979, financially straitened, he sold eight of his designs and his briefcase to the Victoria and Albert Museum, some of which were included in the Art's Commission's exhibition Thirties: British Art and Design. One source mentions that he lived in "Tunley House (part of Tunley Farm) between 1937 and about 1965." ("Can you help?", What's Off in Oakridge Lynch; Far Oakridge, Waterlane; Bournes Green & Tunley, June/July, 2020, p. 7)

Denham's style is strikingly original at a time when so much of what was happening in design was original. Of his furniture, Duane Kahlhamer writes, "Maclaren stands out from that of his professional contemporaries during the interwar period of the 20th century." (Kahlhamer, p. 143) The Victoria and Albert Museum proclaim that "he of all British designers captured the spirit of contemporary European modernism. He followed the functionalist precepts of Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius, and most of his furniture was constructed of steel and glass." However, they also note that while "he used materials in new ways, he did not investigate their structural possibilities like the functionalist wing of modern design". (Paul Greenhalgh, "British Modern Furniture Designers," Antique Collecting, March 1992, cited on the Victoria & Albert Museum Website, gathered 3/25/25)

Maclaren worked in a variety of materials,

Plate Glass-Sided Chairs, Leather, Chromed Metal and Wood Frame, c. 1930, Instagram

but the media took particular notice of his use of glass in furniture during 1929. The Czech journal Výtvarne Snahy (Art Endeavours) said that "his products are formally very individual. These items in England today, I suspect, are the first attempts at metal and glass furniture, which until now find use in beauty parlours, exclusive offices and in mansions." ("Nabytek v soucsne Anglii" (Furniture in Contemporary England), cited Kahlhamer, p. 147) A newspaper noted that Maclaren "is exploring the possibilities of all kinds of glass furniture, is at present at work on a design for a glass armchair, the first of its kind ever contemplated. ...It yet remains for Mr. Maclaren to design a glass bed and a glass sofa." ("The All-Glass House", The Penrith Observer, cited in Kahlhamer, p. 149) An example of his class chair can be seen at left. Decoration magazine said his use of plate glass "appears to be unprecedented. Expensive, and mostly reserved for the relatively new building types of department stores and showrooms, the material properties of plate-glass were particularly fascinating to the public." (Michael McCollum, "The Age of Glass", J. Andrew, Decoration, March 1936, p. 13, cited by Kahlhamer, p. 150) He was exposed to plate glass through his work on displays for Arundell.

There is a limited amount of Maclaren's work, probably because much of it was created for individual commissions or displays, which is typical of many Art Deco pieces created in the 1920s. He similarly designed individual pieces for his remodeling of the of 52 Grosvenor Street. The V&A Museum explains, "Maclaren's most innovative designs were produced during the mid 1930s mainly for his own pleasure, they remain amongst the only pieces produced in Britain that can stand alongside Modernist design on the Continent." (Greenhalgh, cited on the Victoria & Albert Museum Website) Kahlhamer agrees that his output was limited, "and fewer designs were suitable for mass production. Maclaren's wooden furniture would have been produced by skilled craftsmen on an ad hoc basis and some were made only as unique pieces." (Kahlhamer, p. 143)

Sources Not Mentioned Above:

Denham's White House, Denham History Online, gathered 3/25/24

Pinterest Glass Chair

Original Facebook Group Profile

Andrew Maclaren Furniture, From Left: Desk, Glass, Wood and Chrome, c. 1929, V&A Museum; Occasional Table, (Side and top), Glass and Chromed Steel, 1929, V&A Museum; Side Table, Rosewood Veneer, Copper Tube, c. 1930, Bonhams; Armchair, Glass, Metal, Zebra Skin, c. 1930, V&A Museum; Dining Table, Textured Glass, Wood, Coppered Steel, c. 1930, Artnet

Andrew Maclaren Furniture, From Left: Desk, Glass, Wood and Chrome, c. 1929, V&A Museum; Occasional Table, (Side and top), Glass and Chromed Steel, 1929, V&A Museum; Side Table, Rosewood Veneer, Copper Tube, c. 1930, Bonhams; Armchair, Glass, Metal, Zebra Skin, c. 1930, V&A Museum; Dining Table, Textured Glass, Wood, Coppered Steel, c. 1930, Artnet