Jacques (1900 - 1984) and Jean (1900 - 1995) Adnet

Twins Jacques and Jean Adnet, Wikipedia and Docantic

Jacques Adnet (1900 - 1984) and his twin brother Jean (1900 - 1925) were French Modernists who worked together for many years. Jacques was the eldest by 90 minutes, ending up as the dominant twin. In their careers, Jean focused primarily on painting, sculpture and set design while Jacques focused on furniture, rooms and architecture. "The twins' predispositions to plastic creation, noticed early on, led them to attend the municipal drawing school1 of that same town from their adolescence, alongside their secondary studies at the Auxerre college." (Alaine-Rene Hardy and Gaelle Millet, Jacques Adnet, 2009, p. 16) At the age of 16, they passed the entrance exam to the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, moving to Paris to study architecture at the school. They were introduced to interior design by painter/decorator Felix Aubert. Jacques completed his training with decorators Henri Rapin and Tony Selmersheim. Upon graduating, the brothers were hired by Selmersheim.

In 1922, Dufrène was appointed director of Studio La Maîtrise, which designed decorative arts for the Parisian department store Printemp. Jean and Jacques joined him. Dufrène "particularly appreciates them for their willingness to go, in the artistic field, always further and elsewhere". (Hardy and Millet, p. 22) In return, the brothers saw Dufrène as "their guide and their friend. Both found in the qualities of mind and knowledge of this 'patron' happy and profitable examples." (Hardy and Millet, p. 26) During this period of their career the twins always worked together, going so far as to sign their work 'J. J. Adnet', J. - J. Adnet or J. and J. Adnet. People sometimes confused their work as having been produced by one person, Jean-Jacques Adnet. The furniture they produced during the mid-1920s updated and simplified the ornate traditional furniture which had been popular, placing an emphasis on materials such as leather, metals, mirror, and wood.

Their work appeared in the touchstone 1925 Exposition Internationale

Two of the Four Crackled Ceramic Pigeon designs for the Lady's Bedroom at

the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs (1925) 1st Dibs

des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes which introduced what is now called Art Deco to the world, exhibiting four decorative panels in the men's bedroom in the Lafayette Galleries exhibit, likely wood, including representations of discus throwing, high jumping, pole vaulting and hammer throwing. They also provided four sculptures of pigeons which appeared in the lady's bedroom as well as a carpet which appeared in the hallway of the display. Dufrène also had a small artist's apartment display containing five rooms in the Esplanade des Invalides. The design of this apartment was left to his young collaborating designers. The Adnet brothers were given a 'rest stop' for drivers to design including the furniture, carpets and artwork. Unfortunately, the details of this room are not known.

A. Lusca (A. is probably 'Auguste'), producer of ceramics also displayed at the Exposition in the Grand Palais. He produced ceramic pieces for the the Adnet brothers which appear to have been independent of La Maîtrise. Lusca devoted a showcase to their ceramic creations including porcelain pieces, crackle vases, boxes with black enamel and very decorative earthenware with polychrome enamel. Although not represented at the show, the Adnets seem to have also been producing rugs independently of La Maîtrise studio

Even after the 1925 Exposition, the Adnets were primarily given small pieces to

Part of the Adnets' Modernist Library/Smoking Room for the 1927 Salon d'Artists in Paris

Photo by Therese Bonney, Smithsonian Library

design at La Maîtrise such as small ceramic pieces, rugs and small pieces of furniture. During this time, the brothers began shifting their style away from the traditional style typically displayed at Salons and Exposition by Dufrène's La Maîtrise studio and moving more towards Modernism. At the same time, Jean's talent for creating store windows dressings began being recognized during this time, being regularly requested for such jobs at the studio.

Jacques was awarded an official travel grant in 1926, leading to his receiving the Blumenthal prize in 1927. Some sources indicate that the prize was given to both brothers. (See "Jean Adnet", Docantic website, gathered 8-5-24) It is quite possible that this was the case, given the the brothers had always worked together during the preceding period. (Note that as of this writing, the Wikipedia entry for the prize indicates that Jean won it in 1923, which is incorrect.) The Blumethal prize was a grant awarded to young French artists to help draw the United States and France closer together through the arts.

At the 1927 Salon d'Autorne, the twins created a library/smoking room which was financed by La Maitrise, perhaps in some recognition of their achievements. The furniture had sharp edges and mirror-like appearance provided by Duco lacquer. The effect was clean, functional and not a little industrial, embodying the ideals of Modernism. "...it was certainly ...qualities such as the coherence of forms and the precision of the management of volumes that earned the twins a distinction from the Society for the Encouragement of Art and Industry, which awarded them a gold medal for this presentation." (Hardy and Millet, p. 44)

Adnet Window Display, La Grand Miason de Blanc Department Store, Photo - Therese Bonney, c. 1926,

Smithsonian Library

They went in different directions in 1928 when Jacques was appointed Director of the Compagnie des Arts Français. Jean remained at La Maîtrise where he was appointed director of the important display department, a position in which he focused on the art of designing window displays. He also participated in exhibitions of decorative art with high-quality furniture. "[H]e was one of the first to renovate, almost invent, the art of window displays, disrupting routines and prejudices, and creating a 'street museum' that demand[ed] the skills of a stage director from the decorator. It requires imagination, fantasy, and attentive opportunism, constantly tested against the fluctuations of fashion and seasons. The means of expression, such as light, color, shape, and accessories, are both intangible and material, and the artist must manipulate them like a realistic magician." ("Jean Adnet", Docantic) The majority of his artwork was in the areas of painting and pottery.

Jean was later asked to teach the students at École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs about his window dressing techniquea as well as taking on official responsibilities at the organization of the International Textile Exhibition in Lille in 1950 and the Union of Textile Industries in London in October 1954. He continued designing furniture and took on carpets commissioned by Jacques for the Compagnie des Arts français. He never stopped painting, exhibiting his work at the Salon d'Automne, and the Salon du Dessin et de la Peinture à l'Eau.

Jean's Artwork, from left - Sculpture of Woman, Ash, invaluable; Seascape Painting, Oil on Canvas, Oger-Blanchet; Jean & Jacques, Vase, Porcelain with,

Jean's Artwork, from left - Sculpture of Woman, Ash, invaluable; Seascape Painting, Oil on Canvas, Oger-Blanchet; Jean & Jacques, Vase, Porcelain with,Enamel Decoration, 1925, Invaluable; Jean & Jacques for Lusca, , Dish with Birds, Glazed Ceramic, 1925, Ebay, Jean & Jacques, Earthenware Vase with

Orange Swirls, Black Leaves and Green, Before 1928, Biron

Jacques' appointment to the directorship of the Compagnie des Arts Français (CAF) came as company founders Louis Süe and André Mare were losing money and arguing with each other. Due to the financial difficulties, shareholders of the company decided to sell their majority stake to businessman Théophile Bader. Mare's health was declining. When Süe resigned from the company in 1928, Bader chose Jacques to head the company based on the recommendation of Maurice Dufrène.

Although Jacques became the company director, he actually shared direction of the company with Bader and Dufrène. Apparently with their blessing, he began moving the company towards the

Jacques Adnet, Settee and Sideboard, Wood and Shagreen, Reupholstered Blue Fabric

(c. 1934)

style for which he is today most recognized - avant-garde in a way which didn't upset the public supporters of the company's founders Louis Süe and Andre Mare. CAF's focus gradually changed from the traditional French style of the founding duo towards "clean, unencumbered forms with a rigidly functional aesthetic which could fit any purpose or environment. While his decorative element was smoked glass, Adnet incorporated precious woods, such as peroba and bubenga, chromed metals and embellishments such as mirror, leather, shagreen (galuchat) and parchment in linear styles with decoration pared away wherever possible." (The London List). Adnet collaborated with a variety of other decorators in the process with his inner circle including Dufrène, his brother Jean as well as designers Charlotte Perriand, Paul Pouchol, Francis Jourdain, Suzanne Agron and Suzanne Guiguichon, among others. (Hardy and Millet, p. 64, citing an article by Ernest Tisserand). Jacques also collaborated with notable artists including Raoul Dufy, Fernand Léger, Marc Chagall and Alexandre Noll as well as a variety of ceramic artists, coppersmiths, goldsmiths, tapestry makers and decorators. He also brought Jean's son Oliver on board.

Jacques also changed the method of production.

[F]aced with a growing demand from customers, he chose to exhibit and sell creations and decorative objects designed by members of the Compagnie des Arts Français [which were] mass-produced to be more accessible to the greatest number [of people]. ...The Compagnie des Arts français also participated in a certain democratization of the decorative arts, offering its customers the possibility of providing some modernity to their interior by the simple acquisition of small utilitarian or decorative objects in relation to their budget. In this, the break with the practice of the former management [Süe and Mare] appears profound... (Hardy and Millet, p. 68-9)

This should not be entirely surprising. The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 made it necessary for most designers who wanted to continue in this field to stop focusing on handcrafted furniture for wealthy individual clients (who were understandably straightened by the financial collapse) and move towards designing less-expensive, mass-produced products accessible to regular consumers. Indeed, this was to be a period of intense re-development of the CAF's offerings.

Like other artists and companies, Adnet promoted

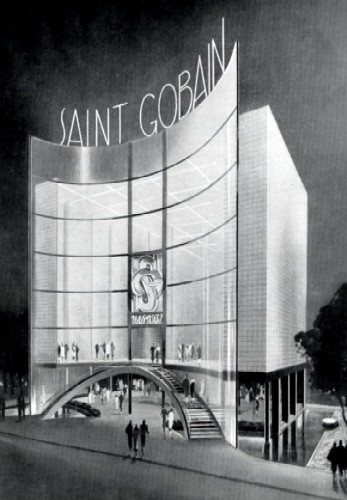

Saint Gobain Building, Exposition Internationale (1937)

From Saint Gobain

Promotional Material

the CAF designs at exhibitions and salons...eventually. The company was already committed to the spring Salon des Artists Decorateurs, so Jacques oversaw the CAF display there in 1928. However, they skipped the next several exhibitions, reappearing at 1932 Salon des Artists Decorateurs. During the break, Jacques was "restructuring the catalog, and intensely creating all kinds of objects necessary for the equipment of the house: lighting, carpets, decorative trinkets, not forgetting isolated furniture." (Hardy and Millet, p. 71) Going forward, he created CAF's most important displays at this Salon, while also offering representative pieces at the Salon D'Automne and Les Expositions des Arts Decoratifs. In 1932, he also displayed at "Metals in Art" Exhibition, showing furniture with chromed tubing and mirrors. He again exhibited such furniture at the 1934 "Glass. Mosaic and Enamel" Exhibition. The press generally treated the CAF displays favorably.

The 1937 International Exposition Arts et Technologies dans la Vie Moderne was one of the series of exhibitions which followed the seminal 1925 International Exhibition. The focus of the Exposition was broadened beyond interior design to include the general environment of modern life - electricity, hygiene, aeronautics, cinema and tourism. Adnet presented several displays here on behalf of CAF, earning grand a prize for Furniture Ensembles.

Working with René Coulon, Jacques was commissioned to design the Saint Gobain glass company pavilion for the 1937 International Exhibition of Arts and Techniques. The resulting glass palace required him to exercise architectural techniques in creating the avant-garde structure. It was designed to show various ways in which Saint Gobain's products could be used in building, including large glass slabs cast on a bed of sand, glass blocks and tempered glass. Adnet and Coulon were awarded five prizes for the St. Gobain pavillion, including the grand prize for architecture at the International Exhibition of Arts and Techniques in Modern Life.

When France became involved in the war in September of 1939, the company ceased operations. Jacques was recruited to help with camouflage design for France. After France surrendered

Chairs with Tapestries of Seasons, (c. 1940), Galerie Chastel-Marechal

to Germany in June of 1940, Jacques was sent home. Despite the occupation, the French managed to hold two annual salons: the Salon d'Automne and the combined Salon des Artistes Décorateurs and Salon des Tuileries. Displays were limited, but Adnet participated. Jacques' career wasn't limited to overseeing CAF. In 1941, likely due to the inability of the company to function, he began teaching at the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs (EnsAD). In 1945, a reform of studies provided him with the opportunity to supervise the fourth year students who were entering their field of specialization. Adnet lectured on the theory and practice of furniture ensembles, a favorite topic of his.

After the war ended, Jacques returned to CAF changing the design style from simple Modernist designs towards more decorative designs which added art and ironwork to furniture. He also began producing tapestries for use as wall hangings as well as on furniture in recognition of this traditional art. "[T]he production he proposed in the 1940s was no longer modernist, far from it; it no longer followed the fundamental principles of this dominant pre-war current such as the absence of ornamentation or the use of industrial materials, but on the contrary implied a return to craftsmanship." (Hardy and Millet, p. 106)

In addition to his direction of CAF, Jacques received several prestigious private commissions. He was asked to oversee the Salon des Artistes Decorateurs in 1947 and '48.

Sideboard, Oak with Metal Decoration, (ca. 1940), Artsy

As the 1940s came to a close people living in the city began to look to the countryside for inspiration. Jacques revamped the decorative program at CAF to embraced this trend, creating simple, elegant designs from wood, metal, rattan, wicker and leather. In the mid-1950s, he added metal and glass designs. Unfortunately, the war had financially weakened CAF resulting in the company's closure in 1959. Jacques also formed a partnership with the French fashion house Hermès during the 1950s, designing leather-covered furniture for them.

On top of his many post-war professional activities, Jacques continued teaching at EnsAD. When director Leon Moussinac retired in 1959, it provided Jacques with the opportunity to put his managerial skills to work in that position now that his company was coming to an end. During his tenure as director of the school, Adnet encouraged students to work with people in other fields, including those from other artistic and design areas, as well as the producers of their designs. His efforts brought about the first industrial design course in France at EnsAD.

From the beginning of his career until World War Two, Jacques Adnet's work became more modernist, rejecting excess ornamentation as well as the flashier materials like ivory, mother of pearl, gilt bronze and rare wood inlays, which were used by other Art Deco designers. "He strove to create practical, useful pieces for everyday life, believing furniture should be functional and geometrically simple. With an oeuvre encompassing the entirety of the Art Deco period, gradually, through his intriguing use of unusual materials, Adnet transcended the genre that nurtured him and moved stylistically towards a restrained, sober modernism." (thelondonlist) After the war, his design style changed from modernist to traditional and neoclassical. Over his lifetime of production, Adnet's furniture embraced a variety of styles and materials.

Other Sources Not mentioned:

"Jacques Adnet", French Wikipedia, gathered 8-5-24

"Prix Blumenthal", Wikipedia, gathered 3-26-25

Original Facebook Group Posting

Jacques Adnet Designs, from left - Wine Caddy, Nickel-Plated Metal, 1940s, Chairish; Side Table, MIrror with Black Lacquered Wood Supports, c. 1935, 1st Dibs; Vanity, Steel Frame, Mirror, Parchment Drawers with Glass Handles, 1930-2, Galerie Lefebvre New York; Chandelier, Silver-Plated Brass, Neon Light with Glass Ball, c. 1930, Chairish; Chandelier, Brass with Chrome Plating, Etched Glass, 1930s, Pamono; Chandelier, Mocle; {;ated Bras amd Cjhrosta;. c/ 1930, 1930.fr

Jacques Adnet Designs, from left - Wine Caddy, Nickel-Plated Metal, 1940s, Chairish; Side Table, MIrror with Black Lacquered Wood Supports, c. 1935, 1st Dibs; Vanity, Steel Frame, Mirror, Parchment Drawers with Glass Handles, 1930-2, Galerie Lefebvre New York; Chandelier, Silver-Plated Brass, Neon Light with Glass Ball, c. 1930, Chairish; Chandelier, Brass with Chrome Plating, Etched Glass, 1930s, Pamono; Chandelier, Mocle; {;ated Bras amd Cjhrosta;. c/ 1930, 1930.fr